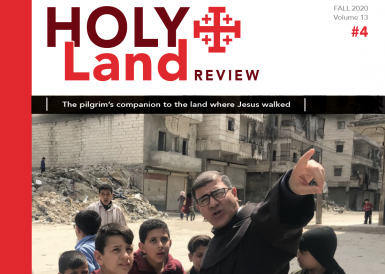

Palestinians return to their destroyed homes in the southern Gaza Strip town of Khan Yunis, July 30, 2024.

© Abed Rahim Khatib/Flash90

One year after “Black Saturday”, and with the number of victims in Gaza exceeding 40,000, how are the Israelis and the Palestinians doing; these two peoples who live in existential fear of being erased? Two psychologists shared with us what is said on the couch of their practice.

By Cécile Lemoine

An Israeli psychoanalyst and a Palestinian psychotherapist face the same questions. Since we were unable to organize a joint discussion, we met individually with each of our two interlocutors: Viviane Chetrit-Vatine, Franco-Israeli and president of the Israeli Psychoanalytic Society in Jerusalem; and Murad Amro, supervisor of the Palestinian Counselling Centre in Ramallah.

What was our idea? We wanted to put into words the psychological impact of the October 7 attacks and the 12 months of war in Gaza. We wanted to understand how each society lives, and sees itself and the other, while these people’s initial traumas are resurrected, identities are heightened and prejudices increased. To get our therapists into the swing of things, we first asked them how they would diagnose Israeli and Palestinian societies.

In Ramallah, at the bustling premises of the Palestinian Counselling Centre, the psychotherapist Murad Amro rises to the occasion; he begins: “I would say that Israel has an obsessive and paranoid behaviour… Obsessive because Israelis have this constant fear of insecurity, to the point that they become obsessed with it and create all kinds of tools to protect themselves. Paranoid, in a psychotic sense. They are not able to connect with the history of the people who live here, and to feel that they are victims of their policies. They are so afraid that they take out their violence on us to protect themselves from their ghosts. But the more aggressive you are, the more anxious you are.”

What about the Palestinians? “The Palestinians were, and still are, hysterical,” continues the psychotherapist, who trained at the University of Montpellier. “In the 1980s, they felt that our situation as victims would help us to plead our case, and to obtain international recognition. They still believe in this discourse, and today the Palestinians are depressed. They see little escape from the current reality and no longer have any illusions about international intervention.”

In Jerusalem, in the quiet of a small office with warm and comforting orange hues, Viviane Chetrit-Vatine also launches into an analysis: “Both societies are deeply traumatized, and when we are dealing with traumatized individuals or groups, it exacerbates pre-existing divisions, but it also creates a very strong cohesion when there is a potential threat.” The psychoanalyst dwells on Israeli society, which she knows better: “The country is made up of people who have been carrying pain, worries and traumas for thousands of years. Trauma is part of the Jewish psyche.”

A “natural laboratory” for the study of post-traumatic stress, Israel employed 13,780 psychologists in its health system in 2022, or 1.4 per 1000 residents according to a survey by the staff of the Central Bureau of Statistics. France has an average of 2.5 per 1000 inhabitants. Several authors have shown how Zionism and psychoanalysis were constructed in relation to each other, notably under the influence of Sigmund Freud. Haim Weizmann, a Zionist leader and future president of the State of Israel, wrote in his diary in 1922 that “destitute immigrants from Galicia arrived in Palestine with only Marx's Das Capital in one hand and Freud's The Interpretation of Dreams in the other.” The Israeli Psychoanalytic Society was founded in 1934 by Max Eitingon, who was close to Freud, and today has nearly 300 members.

Feeling helpless

In the Palestinian Territories, psychology arrived later and its relationship with the inhabitants is less instinctive. Palestinian culture struggles to talk about trauma and only 34 qualified psychiatrists work for the Palestinian Ministry of Health. “For a long time, psychiatric hospitals were seen as places reserved for the insane,” explains Murad Amro. “Problems were solved with family or friends... The older generations don't talk much about their emotions.” The Palestinian Counselling Centre was founded in 1983 in Jerusalem, under the influence of the development of Western theories on post-traumatic stress, and remains today the main psychosocial care facility for the West Bank and Gaza. The Centre employs about fifty people, between the offices in Jerusalem, Ramallah, Nablus and Qalqilya.

In this context, we wanted to know what Palestinian and Israeli patients have said or shared in consultations since October 7. Bringing together 10 months of work, Viviane Chetrit-Vatine sums up: “The general impressions are that time has stopped, and there is a collective hostage-taking.” Since October 7, her offices in Jerusalem and Tel Aviv have been full. “Everyone is affected,” she explains. It's a small country: everyone knows someone who has been taken hostage, or who has been killed on a kibbutz, or who is a soldier in Gaza.” The psychoanalyst has even resumed consultations with former patients. “I am dealing with people of all political persuasions. Some are clearly in favour of war and believe that there is no other solution. In general, there are family stories related to the Holocaust behind it. Others are focused on the fact that the first thing to do is to free all the hostages.”

“The patients all express, in one way or another, fear, pessimism and above all a strong feeling of fatigue and powerlessness: you can shout and protest all you want, it's not much use,” continues the psychoanalyst. “At the same time, there is also a terrible malaise in relation to Gaza. But it depends. Not everyone is able to hold all these elements together: when you have a strong feeling powerlessness, the reflex is to hold on to your positions. These are defensive reactions, linked to the fact that we are in great uncertainty about the future.”

Solidarity and human connections

Powerlessness is also a feeling shared by Palestinians during their consultations at the Counselling Centre. “Whether in Gaza or the West Bank, the main emotion is that of loss of control,” Murad Amro said, running a hand through his salt-and-pepper beard.

“In times of war, all symbolic and social structures collapse, people are lost, hope and fear grows and powerlessness too. In Gaza, people are destroyed, physically and psychologically. Israel's disproportionate response to the October 7 attacks has reactivated the trauma of the Nakba. In the West Bank, people are wondering: should we leave? Many express the impression that they are going to be next, that Gaza is only one step in the project of total control of the land by Israel, and that they have nowhere to go. There is also a form of anger that is expressed against the divine: Where is God, and why does he let it happen?”

While Israelis and Palestinians live in existential fear of being erased, how do we deal with trauma, individual or collective? It is this last question that we submitted to our therapists. “There is no miracle cure,” sighs Murad Amro, before mentioning the work of Samah Jaber, president of the mental health unit of the Palestinian Ministry of Health. She believes that it is impossible to adapt Western therapies to her society, since it has been living in “continuous trauma” since 1948. She speaks of “chronic traumatic stress” and insists on the power of solidarity and “soumoud” in her work. A key concept of Palestinian values, the “soumoud” describes the perseverance, resistance through the very existence of the Palestinian people.

Viviane Chetrit-Vatine also talks about the importance of human connections in the healing process. “The protests against Bibi play this role. They permit crying out in discomfort and allow restraint of emotions.” The psychoanalyst also wants to emphasize that in parallel with pain, she has observed a great artistic production in post-October 7 Israel: “Transforming death instincts into life instincts requires inner resources and a form of well-being.” A situation in which Israelis and Palestinians remain, in many respects, unequal.