For 30 years Daoud Nassar has been fighting to retain ownership of his farm, called the "Tent of Nations", located in an area called Bethlehem Heights. Despite administrative and physical pressure from Israel which is seeking to reclaim these lands, he has chosen nonviolent resistance, in accordance with his faith. It’s a powerful testimony.

- By Cécile Lemoine

If hope had a form, it would be that of the tender new green leaves budding on the branches of the charred olive trees on the Nassar farm. Only a few trees with scorched leaves and blackened coal-like earth remain on their terraced land. Last May, this Palestinian Christian family saw more than 1,000 of its fig trees, almond trees, vineyards and olive trees go up in smoke in a huge fire, that was purposely lit. By whom? Daoud Nassar and his wife Jihane, heads of the family farm, have their ideas on the issue: "Palestinians from the village below, probably paid by the State of Israel to try to drive us off our lands."

This is a hard blow for the couple who sees in this gesture an escalation of pressures and injustices which they have suffered for 30 years, usually at the hand of Israeli settlers.

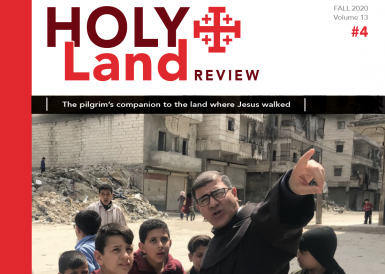

There’s a quiet strength beneath his worn leather hat; Daoud wants to be as resilient as the tender new growth of his olive trees. A man of action, looking to the future, he will not give up on his land or his principles: "I do not intend to sit and wait for things to get better all by themselves. I have to act in my own small way, without hate, without violence". He scrutinizes his farm, the Tent of Nations, with a glance and a gesture. "I call it ‘hope in action’". It’s more than a slogan; it is a philosophy of life, anchored in his Christian faith and long years of battle to preserve the ownership of a land that has belonged to his family for more than 100 years.

The Nassars’ story begins like that of many Palestinians. In 1916 Daoud's grandfather, Daher Nassar, bought a plot of land on top of a hill a few kilometers east of Bethlehem. He then did two things unusual for the time: he registered his property with the Ottoman authorities and then with the British when they took control of the region in 1920; and he also decided to live on the farm, in one of the many caves on the land.

"Selling your land is like selling your mother”

From their hill, the Nassars watched the Nakba of 1948, the beginning of the Israeli army's occupation of the West Bank in 1967, and they were there when the settlers’ expansion started in the 1980s. Soon five colonies with their distinctive red roofs surrounded the farm. These settlements form the third largest block of colonies on the West Bank and the only obstacles to their being interconnected are the Nassars’ farm and some Palestinian villages. Israel then unsheathed its favorite weapon. In 1991 it, declared the region "State Land", manipulating the Ottoman law and allowing the Jewish state to recover land when the inhabitants are unable to prove that it belongs to them. And often they are unable to provide proof, because, to avoid paying taxes to the Ottomans or the British, the Palestinians did not register their land assets.

Only the Nassar have taken the steps and have the papers to show that the land belongs to them. For twelve years, court sessions have followed one another, only to have the family be told that their documents are not sufficient and that their land would be confiscated or would have to be repurchased. "Selling your land is like selling your mother": Daoud refuses. The Nassars appealed to the Israeli Supreme Court, which decided in 2007 to allow them to renew the registration of the property. But there is complete silence from the military authority, which administers the area on which the farm is located. In 2021, after more than $170,000 spent in an endless legal battle, the family is still waiting. Thirty years after the proceedings started, the State of Israel still has not recognized that they really are the owners of the land.

To this mental and financial burden is added the weight of a daily life marked by violence and intimidation. The Nassars explain that there is regular uprooting of their fruit trees by the Israeli authorities or by the inhabitants of neighboring settlements, damage to their reservoirs for water, and blockage of the most direct roads to the farm. "They try to make our lives difficult and try to cut us off, so that we are forced to leave." The most recent abuse, the fire of May 2021, have left Daoud and his wife speechless. "Because it is so dry here and the trees take years to grow, our lives are very connected to them. This makes it very difficult to understand the Palestinians’ action, since it serves Israel's colonial policy," says Jihane, who struggles to hold back the emotion welling up in her big soft eyes. "What we're going through lately is too much."

Resiliency and positive energy

Although the pressures experienced by the Nassars are shared by many inhabitants of Area C (that part of the Palestinian territory entirely administered by Israel), it is the Nassars’ way of dealing with them that is different. "Some people think that violence must be answered through violence. Others feel sorry for themselves and wait for help from the international community. Still others give up and leave the country”, Daoud Nassar relates. “We prefer a fourth path, that of resistance non-violent and active hope”; he hammers out: “We refuse to be the enemies."

The word Bishara, “good news" in Arabic, painted on a stone at the entrance of the farm, are the legacy of Daoud’s father. Long before the idea became popular in Palestine, Bishara Nassar, taught his three children a theory of non-violence rooted in his Christian beliefs and values. "My father was convinced that Christians had a role to play in building a more peaceful future,” recalls Daoud with a bit of melancholy. “He often said that peace would not come from a handshake between Israel and Palestine, but from the base, from the people who populate this country."

Bishara Nassar had a dream. Make the family farm a place to experience and to establish peace, make it a place of hope and reconciliation. His children, and in particular Daoud, took up the torch and opened the "Tent of Nations" to everyone in 2002. Daoud, marked by his years of study in Austria and Germany, brought back the very Western concept of empowerment. The somewhat difficult notion to translate can be defined as a reclaiming of power through self-fulfillment and education. Daoud and his wife have no shortage of ideas to restore hope and teach resilience to young Palestinians: summer camps for young people, training in English and in computers for the women of the village, welcoming volunteers and groups of pilgrims, plans for an environmental education centre ...

If there is one word that defines the Tent of Nations project, it is this: resilience. "It’s a question of using our frustrations and disappointments in a constructive way, to see things in a positive way, rather than becoming a hotbed of anger and resentment,” Daoud explains. It’s a question of absorbing shocks and bouncing back: for example, when being cut off from electricity, they invested in solar panels, the very first installed in Palestine, in 2009; or when, cut off from a water system, they dug 20 reservoirs by hand in the hillside’s rocky ground to collect and store rainwater; or when, for lack of permission to build, they set up their premises in the hill’s natural caves; or when, after the fire in May, they decided not to uproot all the charred olive trees but rather to see if they would grow back naturally ... If hope had a form, it would have the form of the Nassars’ farm.