A long story: The Russian Christian presence is visible in the landscape of Jerusalem,

but the Slavic Israeli believers keep a low profile.

Christian suitcases were among those in the wave of Jewish emigration invited from the Soviet Union. Their number is subject to debate.

While most are Orthodox, Eastern Rite Catholics are also included.

The challenge for these new Israeli Christians is not to consider themselves as Christian but to live in and eventually to transmit their faith to the Jewish state which welcomed them.By Marie-Armelle Beaulieu

In 2006, Israel's Central Bureau of Statistics estimated their number to be 27,000, while researchers said they were at least double that number. On December 21, 2022, the same Israeli bureau of statistics estimated their number at nearly 45,000 but observers say that the number is still underestimated and that we should be talking about 70,000 to 100,000 people.

The number of Christians, who arrived along with the luggage of the large Jewish migration to Israel from the former Soviet Union, remains a mystery and may remain so. Of the million Jews who arrived between 1989 and the year 2000, we have heard that a quarter and possibly even a third are Christians. Up to now, no one seems able to put forth precise and verifiable figures, especially since this vagueness is cleverly maintained by all the parties involved.

Christians in the Jewish Aliyah

The most impressive figures come from Russian sources who declare – off the record – that 70% of the million Jews were Christians! Father Alexander Winogradsky, archpriest of Ukrainian origin, mandated to the Slavic community in Israel by the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate of Jerusalem, unravels this information: "These sources are based on a major event: the millennium commemorations in 1988 of the baptism of Rus. The internal logic of communism collapsed completely. The Church came out of the catacombs and Russia (re)discovered that it was deeply Christian and established on the Christian faith. Then every part of the population went en masse to be baptized, including Jews by the thousands. There were then three million Jews in the USSR and large numbers were baptized." A few months after these mass baptisms, Gorbachev signed the first agreements which paved the way for the aliyah (the ascent) into Israel. According to Father Alexander, only 10% of the Jews from the Soviet Union were able to show the ketubah – the only document that can "prove" Jewishness – and 0% of the Jews baptized in 1988 were able to produce a baptismal certificate since they were not given one.

Even if, at that time, these Jews had been baptized voluntarily, were they practicing Christians? For some, yes.

Rebeca Raijman and Yael Pinsky, authors of an article entitled: "Religion, Ethnicity and Identity: Former Soviet Christian Immigrants in Israel," recall that "Judaism in the Soviet Union was detached from its religious component. Being Jewish meant being a member of an ethnic group (nationality) but not of a religion. Jewish identity was established by descent and persons born to parents registered as Jews were recorded as such on the internal passport." Their field study brought them to meet with Israelis, born of Jewish parents (father and mother), declaring themselves Jews and practicing the Christian faith in the Soviet Union without seeing any contradiction then, just as today in Israel.

Some Jews from the former Soviet Union have therefore made the aliyah to Israel by acting in good faith on their Jewishness while practicing the Christian faith.

Since their religious practice was deeply personal, they would not have mentioned this to the Israeli authorities. Some would not have done so out of habit of saying nothing – they did not live under the KGB for 40 years without consequences –, others might have suspected that some Israelis would not have appreciated the subtle distinction.

Christianity Put to the Test by Israel

The authorities were not completely unaware. Being the first to expand the Law of Return with the so-called grandchildren clause, they expected that those, whom they would later call "non-Jewish Jews", would join the Israeli adventure, and they were also confident that a good program of re-Judaization of these populations would be put in place. According to Raijman and Pinsky, this was done with mixed success. The conversion process demanded by the Israeli Chief Rabbinate was the first obstacle. In reality, the majority had simply become secularized, diluted their ties to Judaism or Christianity, and were making "being Israeli" their new religion. And this suited the authorities very well.

Others have not eliminated Christianity from their lives but have reduced it to a cultural attachment. They have an icon or a cross in their home as well as a Hanukkah lamp (for the Festival of Lights). They celebrate Novy God, New Year’s on January 1st, along with Christmas trees and decorations, as well as Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year.

Some, for whom the Christian faith is important, try to balance two loyalties, to the point of reviving a form of Judeo-Christianity in Israel – fasting for Yom Kippur, having a paschal meal, and participating regularly in the Orthodox Divine Liturgy.

Others have outrightly chosen the messianic tendencies where, in the Hebrew tradition, Jesus is recognized as the Messiah of Israel.

Among the Slavic Christians who arrived during the wave of migration from the former Soviet Union, there are also Christian spouses of Jewish migrants who have continued to practice their Christian faith.

Finally, and perhaps most surprisingly, the "Russian soul" confronted with the Israeli reality led Russians without any Jewish attachment to choose the Christian faith after their arrival in Israel. Thus, Tatiana testifies to her Christian faith: "I came to Israel looking for “Judaism”, I was thinking of converting, but I became more attached to Christianity. It's not a reaction against Judaism, but rather the feeling of being closer to my roots ... Christianity is bound with where I grew up and lived and where my parents lived. There were no Jews in previous generations of my family and Christianity came to me from a deep place inside."

The churches' response

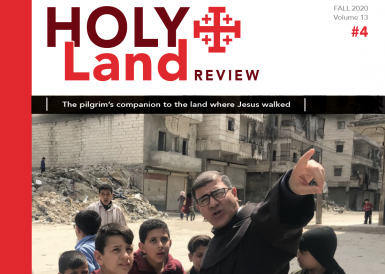

Moscow in Jerusalem. The Divine Liturgy at midnight on Christmas in the

Russian Orthodox Cathedral of the Holy Trinity, behind the municipal buildings in Jerusalem.

Given all these elements, the visits to holy places and monasteries, and the sometimes-explicit request for spiritual accompaniment, the presence of an emerging Christian community in Israel no longer went unnoticed. The Churches ended up working together for these sheep without pastors. The Greek Orthodox Church opened its doors despite its fears of seeing emerge an Orthodox Christian people who were unwilling to follow the Greek tradition. Today on its website – fully translated into Russian – there is a page listing Russian-speaking parishes. There are seven of them. In the region of Galilee, they are served by a Russian-speaking Israeli Arab priest.

All Russian monasteries in the Holy Land have seen a resurgence of attendance and the Moscow Patriarchate has sent reinforcements. For its part, the Custody of the Holy Land, in agreement with the Latin Patriarchate, has brought two Ukrainian Franciscans who serve the Greek Catholic community of Ukraine in Jaffa and Haifa.

But the churches have remained cautious or wary about not appearing to proselytize which is prohibited by law in Israel.

According to Father Winogradsky, alongside this often belated and sometimes apathetic and inadequate response, we have seen priests – sometimes very well known ones – arrive (from Russia) who have come on their own; as well as other members of the clergy possessing various qualifications. To the extent that, today, Father Winogradsky counts "ten illegal patriarchates in Israel and a good fifty (self-proclaimed) bishops who come and go, if they do not manage to get a visa".

These "anarchical" developments are made possible because Russian Israeli Christians want to practice in their Russian language, but they also want to be separate from the Patriarchate of Moscow. In their study, Raijman and Pinsky reported the reactions of believers who deplored being designated as Russian nationalists while they felt themselves to be Israeli, or who criticized the repeated prayers for Palestine while in the middle of Israeli territory. At the very least, indifference to the Israeli reality troubles them although they do not mention the overt anti-Semitism of some priests from the Moscow Patriarchate. Recently, the ongoing conflict between Russia and Ukraine is also reshuffling the cards. Christians of Ukrainian origin who used to attend services in Russian now visit the qehilot, the Hebrew-speaking Christian communities. In this tumultuous faith context and during the search for both national and religious identity, the Christian community with Soviet origins has one constant: its caution. It is difficult, without speaking Russian or Ukrainian, to hear their testimonies. The attendance at the Holy Sepulchre’s night services from Saturday to Sunday as well as the possibility of blending in with Slavic pilgrims in holy places or monasteries continue to be favored by a community that still possesses a catacomb mentality. This is not about to change when a part of the Zionist religious right stigmatizes "non-Jewish Jews" in Israel and makes them a threat to the entire Jewish state, especially those who confess the Christian faith.

In conclusion, Father Winogradsky believes that "it will probably take – as it did for the Hebrew-speaking Christian communities – sixty years to see a uniquely Slavic Christian community flourish in Israel." It remains to be seen whether one day these Christians will feel close, even brothers in faith with the diversity of the Churches already present.