A minority within a minority, the Christians of Ramleh navigate between their desire to integrate into the Jewish majority and their refusal to be identified with Muslims—so much so that some even reject their Palestinian, or even Arab, identity. It is a very intimate inner struggle that is rarely addressed at the collective level.

By Cécile Lemoine

Karlos takes a step back. His eyes widen behind his thin glasses. "How do you introduce yourself? Like a Palestinian, like an Israeli?" Our question panicked him, and the 22-year-old evaded it: "I don't talk politics." "Are you Arab?" "Yes." "Are you Israeli?" "Yes, I am an Israeli Christian." Behind him, the Christmas tree is taking shape. Karlos Amsis is very active in the Latin parish of Saint Nicodemus and has come to lend a hand to finish decorating the courtyard of the church. Karlos speaks Arabic and has Arabic roots. However, he does not define himself as such. Everything, from his reaction to his response, illustrates the conflict of identities that runs through the Israeli Christian community. "It's hard to be a Christian in Israel: in the collective consciousness, the words 'Arab' and 'Christian' are contradictory," said Yasmine Alkalak, who was born in the nearby town of Lod and married to a Christian from Ramleh. "The majority is in charge. Minorities follow the mainstream, without it really being voluntary," says Father Abdel Massih Fahim, the parish priest of the Latin parish.

This distancing from their roots is manifested through another reality: the loss of the Arabic language. "When I visit families and give chocolates, parents say to their children: 'Say 'toda' (thank you, in Hebrew) to Father Abdel Massih," says the Franciscan friar of Egyptian origin. So great is the loss of language that he had to adapt: "In the parish, I have about fifteen children who don't speak Arabic well enough to follow our catechism classes, so I started a course in Hebrew for them. I print Arabic prayers written in Hebrew letters."

Yasmine Alkalak This who works at St. Joseph’s school.

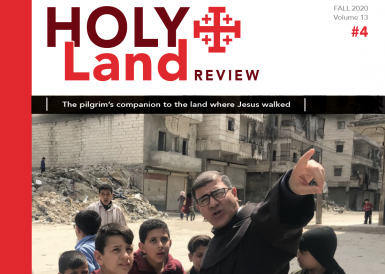

© Photos MAB/CTS

Although this movement can also be observed in other mixed Israeli cities (Jaffa, Acre, Haifa...), it takes on another dimension in Ramleh. Populated by 78% Jews and 22% Arabs, the city is rather poor, and above all plagued by organized crime. "Here, Arab equals Muslim, and Muslim equals mafia," says Sister Muna Totah, principal of St. Joseph's School. "For Christians, the most important thing is not to be assimilated to Muslims," said Vivian Rabia, who proclaims her Palestinian identity and runs the Open House, a center dedicated to Jewish-Arabic dialogue. A rare sight in Ramleh.

Violence, murders, settling of scores, explosions, corruption... Arab mafia clans create fear, and reinforce stereotypes that surface in every conversation. Yasmine Alkalak, who has been substituting for Sister Muna as director of the school since 2017, gives a very concrete example of this distancing: "One year, the feast of the Holy Cross fell on the same day as the Muslim Eid. I wrote a message in the school's WhatsApp group wishing happy holidays to the families of our students, a quarter of whom are Muslims. The Christians reproached me for having put them on the same level as them." "Christians want to be like Jews. They want to be loved, to be modern," agrees Vivian Rabia.

Since October 7, the Israeli psyche has systematically linked the concepts of "Palestine" and "Palestinians" to that of "terrorism." "Israel is a very racist country," said Moussa Saba, a solidly established lawyer and member of the Ramleh city council, who describes himself as an "Arab Christian with Israeli citizenship." To avoid banishment and sometimes arrests, Arab citizens of Israel censor and distance themselves from these causes.

"Identity is not just what is written on a map, it is above all what we feel," says Vivian Rabia. It’s a fluid concept, which shifts and is changed according to life's experiences: identity is a journey. And the Christians of Israel are at a crossroads.

From a small insignificant office, Moussa maintains that the problems of the Christian community are linked to the education system: "There are three private Christian schools in Ramleh. None of them receives the same aid as the other schools. As a result, tuition fees remain expensive (between €1,300 and €1,700 per year per student, editor's note), our teachers are paid less, and parents send their children to Israeli public schools." Yasmine Alkalak has been there. "In the 1970s, families invested in their boys. My brothers went to the Terra Sancta school in Jaffa, but I was put in a government school. For many, it was the only affordable option: there were 20 other Christian students." In Lod, she grew up to the rhythm of the Jewish calendar. Yasmine recalls that "our neighbours were Jewish and my parents wanted me to be normal and, for Purim, my mother would dress me up as Queen Esther". Far from Christianity, she reconnected with her roots when she moved to Neve Shalom-Wahat as Salam with her husband and their two children. This village, a real island of shared life, has as many Jewish inhabitants as Arab inhabitants. "It was like waking up," says Yasmine. I was surrounded by Jews and Muslims who were full of questions about Christianity. I didn't have the answers, so I took four years of religious studies at the Bible College in Bethlehem."

© Photos MAB/CTS

It was a long path that reconciled her with her identity and made her critical of the system: "There is no place for Christianity and its history in government school curricula. In Arab schools, you are told about the history of the Qur'an, and in Hebrew schools, you are told about the history of the Torah. Christianity is only evoked through the prism of the Crusades." As a result, "Our Christian children don't know who they are," laments Sister Muna, since this phenomenon really causes confusion. Originally from Ramallah, in the occupied West Bank, the 43-year-old Sister is Palestinian through and through. "Why confusing? Because they are mixed. They are Arabs, but they are not Palestinians. They are Israelis but they are not Jews. They are Christians, but they live in a Jewish town. In the educational process, the most important thing for the stability of the child is that he knows who he is. The challenge is to be a Christian while preserving one's Arab identity. This is why, at Saint Joseph’s, we have decided to strengthen their Christian identity. That's our goal." We have trickle-down technique: reaching families through children. "I gave a lesson on Arab saints, and the students took the handouts home. The parents have rediscovered these stories and this part of their identity," says the spirited sister.

Father Abdel Massih, the former head of Christian schools in Israel, tried to fill this gap by coordinating the writing of a book on Christian history in Arabic. He is campaigning with the Ministry of Education so that this subject can be presented for exams. But at the Terra Sancta school, adjacent to the parish, questions about identity remain confined to the private sphere: "The children already have a lot of problems, and I have the feeling that talking about it at school would add a new layer of difficulties," says Nisreen Zaarour, director of the school.

While the problem is clearly identified, the answers are still in their infancy. In order to change this, Vivian Rabia, an inveterate communist who has always kept her distance from ecclesiastical institutions, agreed to join the council of the Orthodox Church of Ramleh. Although she is single, she is concerned about her nephews and nieces’ development: "They want to be rich, they want to travel, they write to me in Hebrew... No matter how much Christians try to integrate, in the end, we will always be different, we have to be aware of that," says the jet-haired sixty-year-old. While Christians may succeed in integrating on an individual level, collectively the process has failed, because it comes at the cost of a loss of identity." Moussa, Yasmine, Vivian, Nisreen... All of them say they are now comfortable with their Arab identity. They had the space and the means to think about the subject. But this generation, which grew up in the 1970s, in contact with grandparents who lived through the Nakba, is not the generation that is growing up today with social networks.

Terre Sainte Magazine, #701, Jan-Feb 2026