wall reveal the true desire for a single state without borders?

At a time when the so-called "two-state solution" is under attack on all sides, the meeting with yesterday and today’s Palestinian activists adds a different perspective on what was thought to be known about their own expectations. What if living in peace on the land where they have always lived, recognized for who they are, with equal rights, was enough for their happiness today?

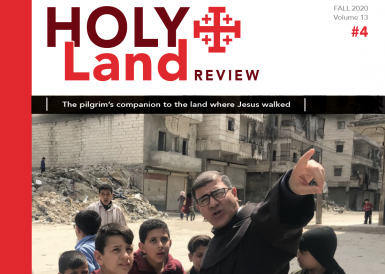

- By Karine Eysse

When a Palestinian discussing politics laughingly raises his eyebrows and says that with a little luck Israel will annex the Territories, and that then he will be an Israeli – khalas! (Arabic for “it’s over!”) – and that the conflict will be done, we should not take this show of humor at face value; but neither should that prevent us from considering all the contradictions and bitterness that exist. A joke sometimes says more than a long speech; and speaking about a "two-state solution" begets a variety of responses across a Palestine where official doctrine seems to remain untouchable. Palestine is fragmented: the most notable divide is, of course, the one between the West Bank and the Gaza Strip.

In the West Bank, the official position, from the international community’s point of view, is put forth by the Palestinian Authority (PA), which is controlled by the elderly President Mahmoud Abbas’ Fatah [liberation movement]. Presently, it is impossible to go beyond the influences of the historical leader and tutelary figure of Palestinian liberation and founder of Fatah, Yasser Arafat. In November 1988, Arafat accepted UN Resolution 242 in the Palestinian National Council, which for the first time implicitly recognized the State of Israel, while proclaiming the Palestinian State. The signing of the first Oslo Accords in 1993 confirmed this path: the two-state solution therefore appears to be the only viable one for Arafat's heirs.

If we look at the Gaza Strip, despite the border crossing symbolically preserved by the PA with Israeli checkpoints on one side and Hamas on the other, it is obvious that Hamas carries the "official" word in this strip of land barely 360 km² with its 2 million inhabitants.

Hamas' August 18, 1988, charter is clear about its objectives: to regain occupied Palestinian land and to remove the "Zionist entity." It is a position that could not more clearly favor a single Palestinian state, from the Mediterranean to Jordan. But in 2017, the charter was amended: a document completed the original text, declaring itself in favor of recognizing the State of Palestine within the 1967 borders. It was a way to recognize implicitly the existence of Israel, even if the original text of the charter is not suppressed. Therefore, in keeping with this addition to the text, even Hamas would place itself in the camp of those who support a two-state solution ... nevertheless, the most warlike rhetoric is always quick to resurface during moments of tension.

A weakened position of principle

It is impossible, however, simply to conclude that the Palestinians have consensus on a two-state solution without mentioning the consequences of [Israeli] colonization in the West Bank. According to the Israeli NGO B'Tselem, in 1993, 110,000 settlers lived in the West Bank; but in 2020, there were 662,000. Consequently, there is no longer any territorial continuity within the West Bank itself: settlements and roads are forbidden to Palestinians. And we have not even mentioned the issue of no territorial connection between the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. This reality has obviously not escaped the PA: its Prime Minister, Mohammad Shtayyeh, regularly sounds the alarm on this subject; in fact, even before his appointment, he wrote a book on this subject (Israeli Settlements and the Erosion of the Two-States Solution, 2015).

"If the choice is between one state or two states,

I choose one state" set up on the main road

leading to the West Bank city of Ramallah,

February 23, 2017

A young generation of activists

But it is insufficient to hold to the positions officially defended by the PA on the one hand, and Hamas on the other, even if tempered by the colonization issue. There is a generation of pro-Palestinian activists emerging who are unconvinced by their current political representatives.

Thus, the Advocacy Director of the PIPD (Palestine Institute for Public Democracy), Inès Abdel Razek, frankly reveals the Palestinian population’s reticence to speak about being controlled by Fatah or Hamas. The population sometimes views their representatives defiantly, tired of their past representation, especially with the corruption that has existed. In this context, the idea of reviving the PLO is emerging, to bring together several Palestinian organizations, (re)making it into a dynamic body representing Palestinians internationally, and striving for equal rights between Jewish and Palestinian citizens, even in a single, binational state.

The taboo, if there is a taboo, is therefore lifted. Inès Razek clarifies: "The question is badly asked when we focus on one state or two states; we must change our perspective and ensure that Palestinians have access to their collective and individual rights". For this reason, the new generation says it is ready to go beyond the framework of the "two-state solution", to imagine a binational state, which would guarantee the recognition of the Palestinian identity as well as equal political and socio-economic rights.

The "old wisemen" as a link?

There is a clear divergence between young activists, who promote the struggle for rights potentially in a common state, and political representatives who are attached to [the notion of] two separate states. It may not be insurmountable, however, if we examine the history of the Palestinian struggle.

A former Minister of Culture in the Palestinian Authority and "a member of Fatah since he was 17 years old", Anwar Abu Eisheh, now in his seventies, remembers his first years as an activist when he dreamt with his comrades of a "single, secular and democratic state". He explained that Fatah and Marxist PFLP authorities gradually convinced his generation that the two states were indispensable. This is what he still believes today, but not without allowing himself to envision, once these two states are in place, "in one, two generations", or even more, that there could be convergences between them.

Another well-known figure is Leila Shahid, former Delegate General of Palestine. Last November, she said in an interview with RTBF that, while still calling for the creation of a Palestinian state, she was not sure that it would be "the one we are talking about today". And she suggested thinking about "perhaps a confederation with Jordan, a federation with Syria, Jordan, Lebanon ... If Israel changes its government, why not a federation with Israel too?"

In short, the Moderns hold to "everything, right now” or “not [to delay] too much" for a bi-national, democratic state, where equal rights would be guaranteed. The Ancients, measuring the degree of inequalities needing to be reduced, hold that the two-state solution is the most realistic despite the issue of colonization. Between the two, there is perhaps not so much a difference in final objectives as there is in timing.

Palestinians in Israel and the Territories

A single claim?

In May 2021, accumulated tensions led to a large flair-up in Israel's so-called mixed cities. Until then, it was thought that a peaceful, year in year out, coexistence between the Jewish and Arab populations had been established. But that month, the frustrations of the population’s Arab-Israeli fringe erupted over the reaffirmation of their Palestinian identity, and also over a demand for equal rights with Jewish citizens – political, social, and civic rights and activities. It was as if contradictorily the anger changed into expressions of hope: a claim for equal rights, implies the same state. Who says a claim to national identity necessitates a reflection on two states, and holds to the classic right of a people to self-determination? Isn't this apparent contradiction a reflection of a political moment in which faith in the two-state solution, presented as self-evident, especially after Oslo, is no longer so evident to the younger generation of Palestinian activists?

And are the dreams of these neo-militants ultimately so far removed from those of their elders?